This April Fools’ Day, I’m not planning to pull any pranks. Instead, my plan is to demystify some mischievous Indian ingredients whose names seem to be given with the express purpose of leading you up the garden path. Every culture has eccentrically-named edibles; and we Brits are hardly blameless. Scotch woodcock? Devils on horseback? Spotted dick?? I rest my case, m’lud.

Throughout the world, foodie red herrings are many and varied – and Indian cuisine offers its own fare share. The trick of understanding these treats is simply to delve headfirst into the historical and cultural whys and wherefores of the nomenclature. For lovers of language, a spot of edible etymology is the most delicious diversion around.

Anyone who patronised a British curryhouse pre-1997 when imports were outlawed may well have got their first surprise upon ordering Bombay duck – which of course is nothing of the sort, unless you know of a particularly suspect bird breed that smells more than a little fishy. The term in fact refers to salted, airdried lizardfish that’s fried and served as a snack.

As with many historic monikers, the origins are up for debate. One theory has it that Bombay duck’s curious name came from the delicacy’s city of origin, combined with a corrupted pronunciation of ‘daak’ – the train which transported the treat from West-East during the Raj; although this tale could be as much of a red herring as the dish in question.

You may well question what place ‘juicy balls’ have in your box of Bengali sweets, but there they are – rasgolla in all their glory. Bawdy Brits will no doubt enjoy the double entendre, and, once they wipe the smutty smirk off their face long enough to slip one into their mouth, will enjoy the spherical sugar-soaked semolina-and-cottage-cheese sweetmeats just as much.

Let’s purge all the puerility at once, as I ask you to consider sprinkling a little devil’s dung into your dinner. Asafoetida, or ‘hing’, is the thing that’s had this filthy-sounding moniker foisted upon it; somewhat unfairly, I feel. The pungent resin is an awesome addition to any cook’s arsenal, adding an allium-like element to all sorts of dishes. It also reduces flatulence, a nugget sure to please toilet humourists immensely.

Those of a certain age will remember being threatened with ‘the slipper’ if they lost their composure at inappropriate moments. Perhaps a more appropriate punishment for a foolish foodie would be to have their chappli kebabs whisked away; the meat mixture’s form resembling the footwear it’s named for. There’s more potential kebab confusion with the ‘nargis’ variety that’s named after a flower because of the yellow-and-white centres of these Scotch-egg-like savouries.

Certain enticingly-named savouries you see in the supermarket contain more artificial additives than actual food. On the flip side, there are a couple of Indian items that do precisely the reverse. Plastic chutney and nylon sev sound nigh-on inedible, but are actually perfectly pure and worthy of real relish. The former is a condiment containing crystal-clear, paper-thin pieces of green papaya; whilst the later simply refers to the finest grade of munchy, crunchy-fried chickpea flour noodles.

Contrary to common thought, ‘tikka’ is also a term pertaining to size and shape and not a neon-red marinade with a strength somewhere between the curryhouse ‘korma’ and ‘madras’. On the topic of tikka, classic ‘chicken tikka masala’ is also a curryhouse contrivance, created in exotic Edinburgh from a can of Heinz tomato soup for a fussy customer to sauce up his portion of chicken tikka.

If you’re interested in Indian food, you’ll likely know how far removed the Brindian vindaloo is from the original spicy stew the Goans adopted and adulterated from the Portuguese preparation. But as the name incorporates ‘aloo’, it’s easy to assume the dish must accordingly incorporate potatoes. Not so – on the West coast, the word for ‘potato’ is the Portuguese ‘batata’, and the suffix is a corruption of ‘alhos’, denoting the presence of garlic.

You’d be forgiven for assuming aloo bukhara is also some sort of potato preparation. But these fruity beauties are miles from the humble spud – unless they’re nestled up together in a biryani. The jammy plums originate in Iran, their Urdu name literally meaning ‘potato of Bukhara’. Why name it so? Again, ‘aloo’ is a simple corruption, this time of the farsi ‘alu’ – plum. What a palaver.

There’s another fruit found in the lexicon of the sweetmart. The name of the widely-adored ‘gulab jamun’ translates to ‘rose fruit’; the fruit in question a hi-shine black beauty of the same oval shape and size of the syrup-soaked dumplings themselves. If you prefer a pud of sweet sooji, seek out real Indian semolina sold as ‘cream of wheat, not the durum wheat stuff commonly bought in Britain.

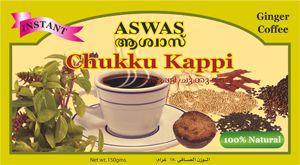

When you quaff a coffee, you kind of know the flavour you’ll be savouring. So allow me a brief chuckle if I should see you sip your first cup of ‘chukku kappi’. The South Indian speciality brings dry ginger, holy basil, black pepper, cumin and jaggery to the brew – undoubtedly tasty, but totally unexpected.

In Britain, mutton isn’t often dressed as lamb, but it sure means sheep; a flavoursome old beast over two years old, long in the tooth, and in need of a good long cook. But in Indian cuisine, the inference is that mutton means kid goat. If the mix up means your meat is goat, don’t bleat at the confusion – just eat up and realise goat is worth getting into in its own right.

Let’s get things right. ‘Roti’ is not ‘A bread’, it’s ‘ALL bread’ – a blanket term for the entire category. Don’t dip your fingers in a dish called ‘navrattan’ in the expectation of digging out ‘nine jewels’ – it’s a mere metaphor for culinary treasures like dryfruits, nuts or veggies. ‘Chickpea flour’ comes not from those fat white kabli channa, but the tiny black variety that’s been split, skinned and ground.

By now, you might feel that the whole Indian culinary lexicon has been created purely to confound you. So to preclude any misunderstandings over motives, allow me to point you to one particular term that not only explains exactly what it is on the tin, but also offers a disclaimer: bitter gourd. When you scrumple your face at the taste, just remember – it did try to tell you.

And I tell you what else; offering that karela to an unsuspecting victim is an excellent prank to play – on April Fools’ Day or any other occasion. Just don’t tell them I told you to do it.

Pingback: Awesome, odoursome ingredients – why ‘cooking ‘curry’ is not a crime) | Culinary Adventures of The Spice Scribe·